Fish Parasites P2

Flagellates:

Flagellated protozoans are small parasites that can infect fish externally and internally. They are characterized by one or more flagella that cause the parasite to move in a whip-like or jerky motion. Because of their small size, their movement, observed at 200 or 400x magnification under the microscope, usually identifies flagellates. Common flagellates that infest fish are given below.

Hexamita/Spironucleus:

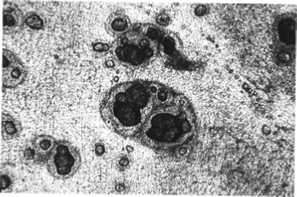

Hexamita is a small (3 --18 m) intestinal parasite commonly found in the intestinal tract of freshwater fish (Figure 10). Sick fish are extremely thin and the abdomen may be distended. The intestines may contain a yellow mucoid (mucus-like) material. Recent taxonomic studies have labeled the intestinal flagellate of freshwater angelfish as Spironucleus. Hexamita or Sprironucleus can be diagnosed by making a squash preparation of the intestine and examining it at 200 or 400x magnification. The flagellates can be seen where the mucosa (intestinal lining) is broken. They move by spiraling and in heavy infestations, they will be too numerous to be overlooked.

The recommended treatment for Hexamita / Spironucleus is metronidazole (Flagyl). Metronidazole can be administered in a bath at a concentration of 5 mg/L (18.9 mg/gallon) every other day for three treatments. Medicated feed is even more effective at a dosage of 50 mg/kg body weight (or 10 mg/gm food) for five consecutive days. See also IFAS Fact Sheet VM-67, Management of Hexamita in Ornamental Cichlids.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Ichthyobodo:

Ichthyobodo, formerly known as Costia, is a commonly encountered external flagellate (Figure 11). Ichthyobodo- infected fish secrete copious amounts of mucus. Mucus secretion is so heavy that catfish farmers popularly refer to the disease as "blue slime disease". Infected angelfish also produce excessive mucus that can give dark colored fish a gray or blue coloration along the dorsal body wall. Infected fish flash and lose condition, often characterized by a thin, unthrifty appearance. Ichthyobodo can be located on the gills, skin, and fins, however, it is difficult to identify because of its small size. The easiest way to identify Ichthyobodo is by its corkscrew swimming pattern. With a good microscope, the attached organism can be seen at 400x magnification. The organism is easily controlled using one application of one of the treatments listed in Table 1.

Piscinoodinium:

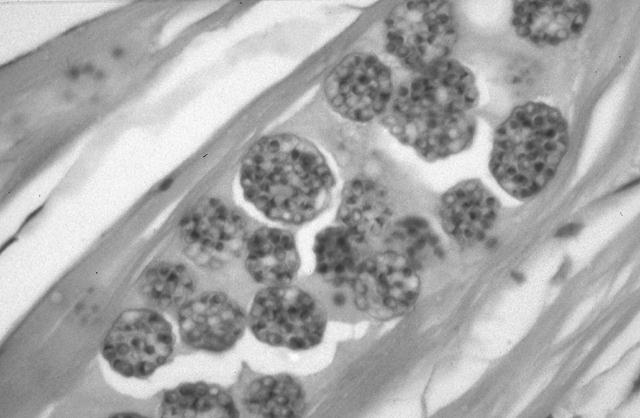

Piscinoodinium is a sedentary flagellate that attaches to the skin, fin, and gills of fish. The common name for Piscinoodinium infection is "Gold Dust" or "Velvet" Disease. The parasite has an amber pigment, visible on heavily infected fish. Affected fish will flash, go off feed, and die. Piscinoodinium is most pathogenic to young fish. The life cycle of this parasite can be completed in 10–14 days at 73–77°F (Figure 12), but lower temperatures can slow the life cycle. Also, the cyst stage is highly resistant to chemical treatment. Therefore, several applications of a treatment (Table 1) may be necessary to eliminate the parasite. For non-food species, chloroquin (10 mg/L prolonged bath) has been reported to be efficacious.

Figure 12

Figure 13

Cryptobia:

Cryptobia is a flagellated protozoan common in cichlids. They are often mistaken for Hexamita as they are similar in appearance. However, Cryptobia are more drop-shaped, with two flagella, one on each end. Also, Cryptobia "wiggles" in a dart-like manner, whereas Hexamita "spirals". Cryptobia typically is associated with granulomas (Figure 13), in which the fish "walls off" the parasite. These parasites have been observed primarily in the stomach, but may be present in other organs. Fish afflicted with Cryptobia may become thin, lethargic and develop a dark skin pigmentation. A variety of treatments are presently being studied with limited success. Nutritional management has proven to take an active role in its cont

Myxozoa:

Myxozoa are parasites that are widely dispersed in native and pond-reared fish populations. Most infections in fish create minimal problems, but heavy infestations can become serious, especially in young fish. Myxozoans are parasites affecting a wide range of tissues. They are an extremely abundant and diverse group of organisms, speciated by spore shape and size. Spores can be observed in squash preparations of the affected area at 200 or 400 x magnification or by histologic sections. Clinical signs vary, depending on the target organ. For example, fish may have excess mucus production, observed with Henneguya (Figure 14) infections.

Figure 14

White or yellowish nodules may appear on target organs. Chronic wasting disease is common among intestinal myxozoans such as with Chloromyxum. "Whirling disease" caused by Myxobolus cerebralis has been a serious problem in salmonid culture. Elimination of the affected fish and disinfection of the environment is the best control of myxozoans. There are no established remedies for fish. Spores can survive over a year, so disinfection is mandatory for eradication.

Microsporidia:

Microsporidians are intracellular parasites that require host tissue for reproduction. Fish acquire the parasite by ingesting infective spores from infected fish or food. Replication within spores (schizogony) causes enlargement of host cells (hypertrophy). Infected fish may develop small tumor-like masses in various tissues. Diagnosis is confirmed by finding spores in affected tissues, either in wet mount preparations, or in histologic sections.

Clinical signs depend on the tissue infected and can range from no visible lesions to mortalities. In the most serious cases, cysts enlarge to a point that organ function is impaired and severe morbidity and/or mortality results. A common microsporidian infection is Pleistophora, which infects skeletal muscle (Figure 15).

There is no treatment for microsporidian infections in fish. Spores are highly resistant to environmental conditions and can survive for long periods. Elimination of the infected stock and disinfection of the environment is recommended.

Figure 15

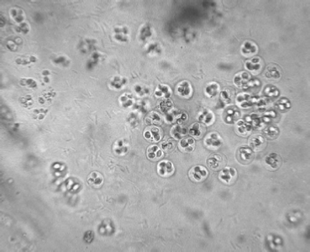

Figure 16

Coccidia:

Coccidia are intracellular parasites described in a variety of wild-caught and cultured fish (Figure 16). Their role in the disease process is poorly understood, but there is increasing evidence that they are potential pathogens. The most common species encountered in fish are intestinal infections. Inflammation and death of the tissue can occur, which can affect organ function. Other infection sites include reproductive organs, liver, spleen, and swim bladder.

Clinical signs depend on target organ affected but may include general malaise, poor reproductive capacity, and chronic weight loss. A definitive diagnosis of tissue coccidia should be completed with histologic or electron microscopy. Several compounds have been used to control coccidiosis with some success; however, consultation with an experienced fish health professional is recommended. Maintaining a proper environment and reducing stress appear to be important in preventing coccidia outbreaks in cultured fish

Monogenean Trematodes:

Monogenean trematodes, also called flatworms or flukes, commonly invade gills, skin, and fins of fish. Monogenean's have a direct life cycle (no intermediate host) and are host- and site-specific. In fact, some adults will remain permanently attached to a single site on the host.

Freshwater fish infested with skin-inhabiting flukes become lethargic, swim near the surface, seek the sides of the pool or pond, and their appetite dwindles. They may be seen rubbing the bottom or sides of the holding facility (flashing). The skin where the flukes are attached shows areas of scale loss and may ooze a pinkish fluid. Gills may be swollen and pale, respiration rate may be increased, and fish will be less tolerant of low oxygen conditions. "Piping", gulping air at the water surface, may be observed in severe respiratory distress. Large numbers (>10 organisms per low power field) of monogeneans on either the skin or gills may result in significant damage and mortality. Secondary infection by bacteria and fungus is common on tissue with monogenean damage.

Gyrodactylus and Dactylogyrus are the two most common genera of monogeneans that infect freshwater fish (Figure 17). They differ in their reproductive strategies and their method of attachment to the host fish. Gyrodactylus have no eyespots, two pairs of anchor hooks, and are generally found on the skin and fins of fish. They are live bearers (viviparous) in which the adult parasite can be seen with a fully developed embryo inside the adult's reproductive tract. This reproductive strategy allows populations of Gyrodactylus to multiply quickly, particularly in closed systems where water exchange is minimal.

Dactylogyrus prefers to attach to gills. They have two to four eyespots, one pair of large anchor hooks, and are egg layers. The eggs hatch into free-swimming larvae and are carried to a new host by water currents and their own ciliated movement. The eggs can be resilient to chemical treatment, and multiple applications of a treatment are usually recommended to control this group of organisms.

Treatment of monogeneans is usually not satisfactory unless the primary cause of increased fluke infestations is found and alleviated. The treatment of choice for freshwater fish is formalin, administered as a short-term or prolonged bath (Table 1). Fish that are sick do not tolerate formalin well, so they need to be carefully monitored during treatment. Potassium permanganate can also be effective in controlling monogeneans

Figure 17